Using evidence from Afrobarometer surveys, the authors analyze public perceptions of security in Nigeria and Kenya and the implications this has on countering violent extremism. They focus on issues of public trust in security forces, corruption and the success and failure of security-led approaches vs development-oriented approaches to violence and violent extremism.

Introduction

Over the past decade, Africa has experienced exponential growth in the geographic spread of violent extremist (VE) organisations and the frequency of attacks attributed to these groups. Boko Haram (predominantly operating in the Lake Chad region) and al Shabaab (in the Greater Horn) are two of the continent’s most active VE groups. Nigeria and Kenya have been particularly affected by these organisations. In both cases, security-led operations against these groups have been mired in allegations of gross human-rights violations, which may well be undermining public confidence and trust in security forces — an important component of sustainable solutions to violent extremism.

While military campaigns and counter-terrorism operations against these groups have periodically produced short-term gains, Boko Haram and al Shabaab are far from defeated; both have proven their ability to adapt and regroup.

Hultman (2007) argues that public trust in security forces has a profound effect on the success of security operations to combat VE in the long term, as it determines whether local communities – who can serve as important allies – are willing to work with or against security forces.[1] Furthermore, the undermining of public trust by security forces through extortion or other repressive abuses may promote VE. For example, as one study shows, “subjection to torture can feed a burning desire for revenge, as well as the broader belief that violence (targeted and/or indiscriminate) may be necessary to ‘purify’ a fundamentally immoral order.”[2]

Furthermore, any short-term gains resulting from military campaigns will eventually need to be converted into comprehensive long-term counter-terrorism strategies, where law enforcement agencies play the leading role. Consequently, public trust in both the military and police are important in creating sustainable strategies for combating VE.

Public opinion data from Kenya and Nigeria in 2014 indicates widespread concern regarding each country’s security situation, high levels of distrust in security forces, and dissatisfaction with government counter-extremist efforts. The survey findings are detailed in a report released by Afrobarometer, a non-partisan research network that conducted nationally representative surveys in 36 African countries in 2014 and 2015.

Security as a public priority in Kenya and Nigeria

Al Shabaab attacks on Kenyan soil began following 2011 Operation Linda Nchi (“Protect the Country”), a joint military operation by Kenya and Somalia to take “coordinated pre-emptive action” against al Shabaab in southern Somalia. That year, al Shabaab attacks in Kenya numbered 38. By 2014, this had increased to 95 attacks, which collectively killed 287 civilians. The group’s deadliest incident to date occurred in 2015 at Garissa University College, killing 148 and injuring another 79.

In Nigeria, police publicly executed Boko Haram’s spiritual leader, Mohammed Yusuf, in 2009. After regrouping under new leader Abubakar Shekau in 2011, the group escalated its insurgency against the state, which reached 456 attacks resulting in 7, 461 civilian deaths by the end of 2014.[3] In January 2015, a coalition of troops launched the West African Offensive, which pushed Boko Haram out of its strongholds in Nigeria’s northern provinces over the course of a few months. However, this precipitated the spread of Boko Haram into neighbouring states in the Lake Chad region (Cameroon, Chad, and Niger).

Afrobarometer data collection took place in Kenya in November and December 2014 and in Nigeria in December 2014 and January 2015. Due to security unrest, it was not possible to conduct surveys in three Nigerian states, so substitutions of sampling units were made from neighbouring states in the same zone to maintain representativity.

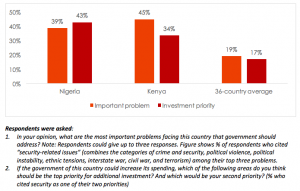

Unsurprisingly, security was a leading priority among the public in both Kenya and Nigeria at the time. When asked to identify the most important problems facing their country, four in 10 Nigerians (39%) cited security-related issues among their top three concerns, while an even larger proportion of Kenyans (45%) said the same. These levels are well above the overall average for 36 surveyed countries (Figure 1), and significantly higher than they were in 2003 (by 26 percentage points in Kenya and 18 points in Nigeria).

Figure 1: Security as a public priority | Kenya and Nigeria | 2014/2015

Similarly, Kenyans and Nigerians were significantly more likely than average to prioritize additional government investment in security: 43% of citizens in Nigeria cited additional spending in security forces as either their first or second choice, while more than one-third (34%) of Kenyans said the same.

Public trust in security forces

As discussed above, building and maintaining public trust in state security forces is paramount to the fight against VE. However, in both Nigeria and Kenya, these institutions have been marred by allegations of widespread corruption, extortion, and human-rights abuses. Thus, increasing spending on security initiatives in both cases may amount to little in the long run if security institutions continue to be viewed with deep suspicion in communities targeted for support and recruitment by VE actors.

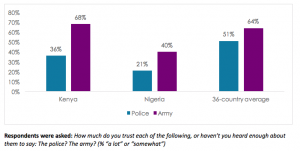

A recent report on institutional trust from Afrobarometer finds that the army is the most trusted state institution in Africa, while the police enjoy considerably less public confidence: On average, 64% of survey respondents in 36 countries say they trust the army “a lot” or “somewhat,” compared to 51% for the police. Kenyans have among the lowest levels of trust in the police force in Africa (36%), but trust in the Kenyan Defense Force (KDF) is much higher than in the police and is above the regional average (Figure 2). In contrast, Nigerians’ trust in both the police (21%) and armed forces (40%) is at the lowest recorded levels in all 36 countries surveyed in 2014/2015.

Figure 2: Trust in the police and army | Kenya and Nigeria | 2014/2015

Counter-terrorism operations against al Shabaab in Kenya have primarily been led by the Kenyan police (spearheaded by the Anti-Terror Police Unit) and the National Intelligence Service (NIS). Both are alleged to have engaged in widespread human-rights violations, including extra-judicial killings, extortion, false arrests, and torture. A study by Edinburgh University, on violence against the urban poor in Nairobi, found that police were responsible for 25% of all violence in the city’s low-income neighbourhoods.

Higher levels of trust in the military in Kenya (and across the continent in general) compared to Nigeria may stem from the fact that the KDF, unlike the Nigerian military, has not been deployed internally. Kenyan civilians are thus not as vulnerable to extortion or the excessive use of force by their military that have characterized internal Nigerian military operations. In Somalia, however, reports allege that “human-rights abuses … appear widespread and are carried out with impunity, including air strikes that target livestock and wells rather than militant training camps.”

A recently published Human Rights Watch report on the Nigerian Police Force (NPF) states that “institutional extortion, a profound lack of political will to reform the force, and impunity combine to make police corruption a deeply embedded problem.” Amnesty International’s 2015 annual report identifies pervasive torture and other forms of ill-treatment perpetrated by the Nigerian police. Nigeria’s Anti-Torture Bill was passed by the National Assembly in June 2015 but has not been signed into law.

The Nigerian Armed Forces’ fight against Boko Haram has been characterized by well-documented gross human-rights violations and the excessive use of force, particularly in the country’s northern provinces, where the group’s activity has been largely concentrated. Amnesty International has gone so far as to say that individual commanders bear responsibility for what amounts to crimes against humanity: “They have extra-judicially killed more than 1,200 people; they have arbitrarily arrested at least 20, 000 people, mostly young men and boys; and have committed countless acts of torture.”

Improving government counter-extremism efforts

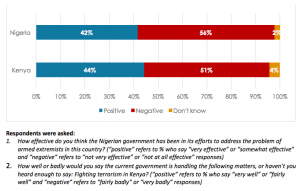

Nigerians and Kenyans were relatively critical of their governments’ counter-extremist programmes in 2014: More than half of Nigerian (56%) and Kenyan (51%) survey respondents gave these efforts negative ratings (Figure 3). This was well above the levels recorded in other sub-Saharan African countries affected by VE, including Niger (2%), Cameroon (13%), and Mali (25%). Approval in Kenya was also low relative to past levels: In 2011, 82% of Kenyans said that the government was doing at least “fairly well” at “addressing al Shabaab.” No comparable question was asked in Nigeria in its previous survey (2012).

Figure 3: Evaluations of government counter-extremism | Kenya and Nigeria | 2014/2015

Despite their criticism of government efforts in 2014, two-thirds of Kenyan respondents agreed that the armed forces’ involvement in Somalia had been necessary despite the resulting backlash from al Shabaab. However, citizens were more ambivalent regarding withdrawal from Somalia: 48% were in agreement with a hypothetical withdrawal, while 43% disagreed.

When asked about suggested improvements to the Nigerian government’s VE response, four in 10 (40%) survey respondents identified strengthening military capacity as either their first or second response. Although this was the highest single response, there was also significant support for non-military solutions such as improving the economy and creating jobs (34%), working together with religious leaders to address the issue (17%), and improving overall government effectiveness or performance (16%).

Over the past few years, Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) has emerged as a developmentally-led “soft approach” that seeks to address root political and socio-economic causes of extremism. As an emergent field of peacebuilding, CVE has become a priority of multilateral organisations and donor countries.[4] Improving relationships between police and the community is often emphasized within CVE programming and framed as fundamental to sustainable efforts to address VE. Consequently, Kenya has seen the emergence of numerous non-governmental CVE initiatives, which include job creation and inter-faith dialogue programmes as core components. In 2014, Nigeria announced its new National Counter-Terrorism Strategy (NACTEST) emphasizing CVE “soft approaches.” However, CVE is not a “quick fix” for VE, and the successes and failures of these ventures may take years to gauge.

Nonetheless, it is clear that both “hard” and “soft” approaches to addressing VE hinge to a large extent on citizens’ perceptions of their security forces. Governments must therefore make greater efforts to build trust between national security forces and local communities and to root out corruption in these institutions.

Public opinion data from Afrobarometer shows that corruption in the police force is believed to be widespread throughout Africa, particularly in Kenya and Nigeria. Almost half (47%) of citizens in 20 sub-Saharan African countries said “all” or “most” police officials are involved in corruption, and the reported bribery rates for public services were highest for police and courts. In Kenya and Nigeria, more than seven in 10 survey respondents believed that at least “most” police officers are involved in corruption (75% and 72%, respectively), while more than four in 10 of those who had contact with the police reported paying a bribe to obtain the help they needed (49% and 45%, respectively).

The Nigerian armed forces have been embroiled in high-level corruption scandals, and several senior army officers have been tried for collusion with Boko Haram. Almost one-third (32%) of survey respondents said they believe that “most” or “all” members of the Nigerian military are involved in supporting and assisting extremist groups like Boko Haram that have launched attacks and kidnappings in the country.

The authors of this blog article have recently published a policy paper on violent extremism in Africa based on evidence from the AfroBarometer’s Round 6 surveys. The report is available here: “Violent extremism in Africa: Public opinion from the Sahel, Lake Chad, and the Horn“.

About the Authors

Stephen Buchanan-Clarke is a master’s degree candidate in security studies at the University of Kwa-Zulu Natal and Project Consultant in the Justice and Reconciliation in Africa Unit of the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation in Cape Town, South Africa.

Rorisang Lekalake is Afrobarometer assistant project manager for the Southern African region, based at the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation and Research Fellow at The Centre for Social Science Research at the University of Cape Town.

Notes

[1] Hultman, L. (2007). Battle losses and rebel violence: Raising the costs for fighting. Terrorism and Political Violence, 19 (2), 205-222.

[2] Wright, L. (2007). The looming tower: Al-Qaeda and the road to 9/11. New York: Vintage Books, p.30.

[3] Numbers were derived using all three criteria used to define a terrorism incident in the Global Terrorism Database: An act must (1) “be aimed at attaining a political, economic, religious, or social goal,” (2) “be evidence of an intention to coerce, intimidate, or convey some other message to a larger audience (or audiences) than the immediate victims,” and (3) “be outside the context of legitimate warfare activities, i.e. the act must be outside the parameters permitted by international humanitarian law” (National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, 2016). Ambiguous cases were included.

[4] The United Nations has articulated its approach to CVE in the first pillar of the United Nations Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy, which is to be implemented by the Counter-Terrorism Implementation Taskforce. In 2011, the White House convened a three-day summit on Countering Violent Extremism, which included President Obama and foreign ministers, to discuss concrete steps the United States and its partners can take to develop community-oriented approaches to “counter hateful extremist ideologies that radicalize, recruit or incite to violence.” Similarly, the European Union has defined its vision for CVE through the EU Strategy on Prevention of Radicalization and Recruitment.

Tags: CVE, kenya, Nigeria, security sector reform

Visit the Centre for

Visit the Centre for